Why Are They Important?

“These are the species that become embedded in a people’s cultural traditions and narratives, their ceremonies, dances, songs, and discourse.” Garibaldi and Turner (p1, 2004)

Cultural Significance

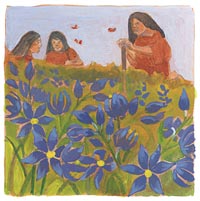

Painting by Briony Penn, courtesy of City of Nanaimo

Garry oak ecosystems are food systems that have been vital to Coast Salish cultures for millennia. Before the arrival of Europeans, these ecosystems were the center of intensive cultivation for important foods and medicines, notably camas (qʷɫəɫ in lək̓ʷəŋiʔnəŋ; KȽO,EL in SENCOŦEN; speenhw in Hul’q’umi’num’) but also including other culturally important species like bare-stem desert parsley and chocolate lily. Coast Salish peoples practiced regular and exacting management that promoted these plants and ultimately shaped the unique ecosystems we know today.

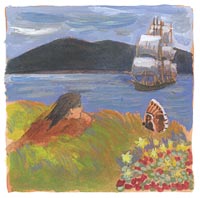

Painting by Briony Penn, courtesy of City of Nanaimo

Camas was not only a staple in Coast Salish diets, but was also an important commodity for trade throughout kin-based trade networks across the Northwest Coast (Turner and Kuhnlein 1983; Beckwith 2004; Proctor 2013). Estimates reckon that a single Coast Salish family could harvest approximately 260 kilograms (8,000-10,000 individual bulbs) each year. The historian John Lutz (2008) states that “Although usually remembered as the “salmon people,” the Straits Salish [lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ] and other Coast Salish groups could just as accurately be called the “camas people.”

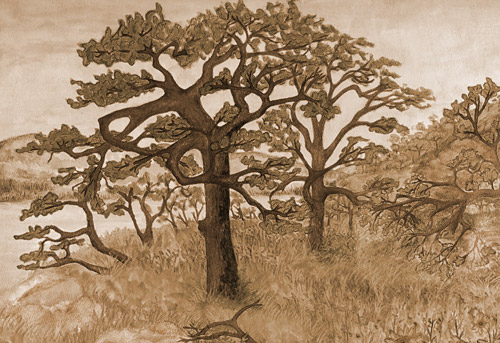

Artist’s rendition of a Garry Oak ecosystem prior to European settlement (by David McPhie)

Biological Significance

Endangered juvenile sharp-tailed snake (photo by Kristiina Ovaska)

Garry oak ecosystems are not well suited to the climate of southwestern BC. These ecosystems expanded during a period of warmer climate, but began to decline with the onset of cooler temperatures around 3,800 years ago (Pellatt and Gedalof 2014). Since that date, the climate has favored infilling of these open ecosystems with trees and the transition to coniferous forest. The cause for their persistence in spite of these conditions is tending and cultivation by Indigenous peoples, particularly through the use of controlled burning. This unique interface of people, care, climate, and place have led to these ecosystems being some of the most biodiverse and rare ecosystems in Canada.

Island large marble butterfly, extirpated from Canada (photo by James Miskelly)

Seven plant associations were developed to describe Garry oak communities, with 17 plant communities and seven sub-communities described. With at least 694 species, subspecies and varieties of plants identified in Garry oak ecosystems, the habitat is home to more plant species than any other terrestrial ecosystem in coastal British Columbia. Many of the species occurring in these ecosystems are at the northern limits of their range, and some are found nowhere else in Canada. At least 55 federally-listed species under the Species at Risk Act, and more than 100 of British Columbia’s at-risk species live in these threatened ecosystems. These habitats also support 104 species of birds, 7 amphibians, 7 reptiles and 33 mammal species. Eight hundred insect and mite species are directly associated with Garry oak trees.

They Need Protection

These ecosystems are threatened by the displacement of Indigenous Peoples, land use change, invasive species, and shifting disturbance regimes. Their cultural role is under threat – connections to these ecosystems through culturally important plants and burial practices are jeopardized by the widespread habitat loss and degradation that has occurred over the last century. If culturally important species that depend on these ecosystems are lost, so are the defining cultural connections.

In parallel, the immense and precious biodiversity that makes up these ecosystems is being lost throughout the Canadian range. However, it is not too late to take action. Working to steward and care for these ecosystems, recognizing that many of us are guests on these territories and in these spaces, can lead to ecological flourishing and assist in a regional movement to decolonize modern landscapes. Therefore, stewardship and protection should be informed by Indigenous knowledge and worldviews in addition to western knowledge wherever possible. Through the principle of ‘Ethical Space’ all knowledge systems are validated and equally valued (Ermine 2007).